Moving into management is tempting to many IT pros. But before jumping into a position you’re not ready for, there are a few issues you need to examine. Review these five steps and decide if you’re prepared to move successfully into management nirvana.

I’ve been fortunate to have managed thousands of employees in my 20-plus years of managing IT resources. One of the interesting things I’ve consistently noticed during that time is how many employees want to become managers.

I’ve been fortunate to have managed thousands of employees in my 20-plus years of managing IT resources. One of the interesting things I’ve consistently noticed during that time is how many employees want to become managers.

I absolutely love managing IT organisations and the people within them, but it’s not all glory and accolades. There is also hard work, frustration, and tremendous challenges required to do the job right. So before you start applying for that open management role, you should take a closer look at the job.

Answering the “why?”

When interviewing or counseling employees, I’m often confronted with someone’s desire to become a manager, and the first question I ask is, “Why?”

The response can provide a useful perspective. Here are a few examples that I’ve gotten over the years:

- “I want to be the boss.”

- “I want the authority and prestige of the position.”

- “I want to direct others on what they should do.”

- “I don’t know; it just seems like the natural course for my career.”

- “I want to attend management meetings and learn what the company is planning.”

- I want to build a big organization

At the time, the staffers who provided these responses didn’t have a clue what an IT manager’s job involved. In fact, most IT professionals don’t, and too many get thrown into management positions with little or no real preparation to do the job effectively.

The answer to “Why do you want to be a manager?” reveals a great deal about what you want from a job and how you view the role of IT in the company. Many technicians see the role as one that defines the technology direction of the company and determines what tools to use. For them, the allure of a management position is the ability to make these decisions. To some extent, that’s true, but many don’t get the fact that what really drives those decisions is the company’s needs and not necessarily the technical knowledge that the manager may possess.

Current competency isn’t all that’s needed

Being good at what you do does not necessarily prepare you for a management position. Let me repeat that: Just because a person is an outstanding consultant or support pro doesn’t mean that the person will be a good, or even an average, manager.

The growth of technology in the last 20 years has created a large demand for more IT managers, and many have found themselves in the role without anything more to help them than what they knew in their former positions.

Certainly, knowing how to program can benefit you in a programming manager role, but it can also be a limiting factor. When you take the best programmers and make them managers, the company and CIO often lose their best productive resources, and a very green person is now placed in a management role that directly influences many others.

For far too many years, it was thought that the best resource in a technical area could effectively manage the rest of the team. That’s not only a false idea; it can also be a dangerous one for the company, the IT organisation, and employees touched by such a move.

The fact is that effectively managing employees and technology resources has very little to do with how technical you are and more to do with your ability to facilitate, persuade, plan, organize, motivate, and communicate. You don’t hear anything very technical in those terms.

Suddenly, what becomes more important is not what you can do yourself, but what you can get accomplished through others.

Suddenly, what becomes more important is not what you can do yourself, but what you can get accomplished through others.

Management is like any other skill. You can learn it, but the key issue is that it’s a different skill set from what you have used as a technician. Of course, the fact that you have been successful as a technical resource does give you a head start, because it helps you relate to others who have technical roles.

When you become a manager, you have to let others do the technical part so you can focus your time and energy on doing the management part. With technology changing as rapidly as it is, you simply cannot continue to be the technical expert and expect to be an excellent manager.

If you take nothing else away from this article, take the message that when you decide to become an IT manager, you have to focus your time and full energy on issues that help you succeed as a manager. If you like solving problems, learning new technologies, and implementing new tools and technology, you may want to stay in your technical role. Managers don’t have time to become experts in the new technologies and do their management jobs well.

Positioning yourself for management

I’m not suggesting that you can’t become a manager if you truly want to. Take my insight as a message to prepare and understand what the job is really all about before taking the leap. It’s not about giving orders and telling others what to do as much as you might think. If that were the case, it would be a simple deal.

Here are five steps to take in your current role to prepare for a management position:

- Learn how to manage projects and establish a successful track record of managing projects that are delivered on time and within budget. Developing sound project management skills is the best preparatory step, as the role requires many of the skills needed in a management position.

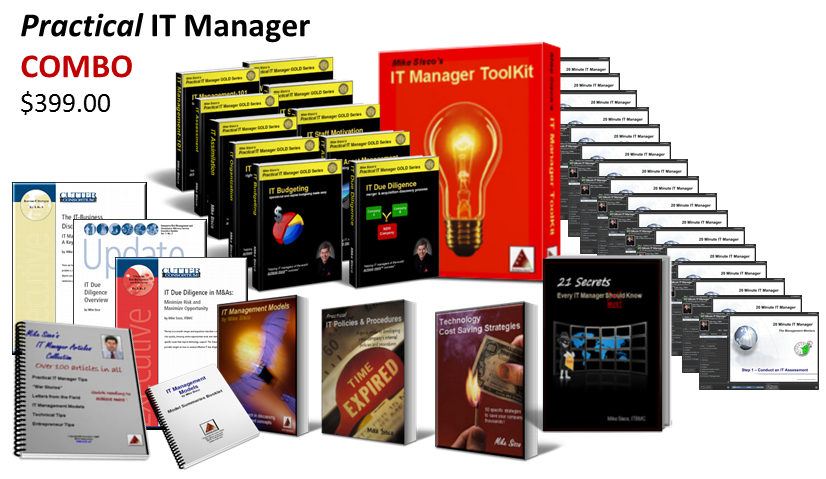

- Observe successful managers managing and motivating employees. When you see something that’s effective, add it to your skills “toolkit.”

- Find a mentor who has a successful management track record and is willing to help you develop management skills and offer you insight. Mentors are invaluable and can help you save time, avoid wasted effort, and reduce frustration because they know the shortcuts that are effective as a manager, just as you know the shortcuts in your technical role.

- Tell your current supervisor that you’re looking to move into a management position and would like help preparing for the new challenge.

- Ask for more responsibility so you can develop new management skills. Be sure you preface the request so that it’s clear that you want it to help you develop skills that will prepare you for a management role.

There’s no quick shortcut

Depending upon your background and experience, you may have a long road ahead in your preparation efforts. Don’t expect to be offered a management position the week after you ask for it. You need to realize that management roles require new skills, so you should be prepared to make the investment to develop those skills.

Over the years, I’ve turned down many management/promotion requests from staffers who were not ready to become managers. But for those who showed a genuine desire to become managers, I made an investment in that goal, and many turned out to be exceptional technology managers. If I had moved them into management roles, unprepared in both perspective and skill set, I would have been negligent as a manager myself and could have damaged their careers.

In every case, the first question I ask is, “Why do you want to be a manager?” In most cases, the initial answer is not the same answer given a year later when they better understand the role.